Living in Mexico Amidst the COVID-19 Pandemic

When I moved to Mexico in 2018, a worldwide pandemic was the last thing on my mind. Of course, it was always a possibility but not the kind of thing you really think will happen when planning a move to another country. Pandemics have been a regular part of existence for as long as there has been life on the planet, but humanity has been fortunate not to have one as devastating as COVID-19 since the “Spanish flu” pandemic in 1918 which killed 300,000 in Mexico and as many as 50 million worldwide.

In fact, pandemics are nothing new to Mexico, which was itself the source of the H1N1 influenza outbreak in 2009–2010. The arrival of the Spanish in Mexico 500 years ago this year introduced smallpox to the continent, a disease that spread in advance of the Spanish themselves, killing up to 40% of the population at the time. The disease plagued Mexico until the development of the smallpox vaccine several centuries later in the 1950s. Mexico returned the favor, sending a North American type of syphilis back to Europe, where it killed thousands. Back in Mexico, there were many other outbreaks of exotic European diseases, including measles (1531) and typhus (1545 ), but the worst pandemic by far emerged in 1576, killing 1.2 million in just one month, amounting to 80% of the remaining population in central Mexico at the time. To this day, it is not understood what caused this pandemic, referred to as cocoliztli by the native people at the time, but the suspects include typhoid, malaria, hepatitis, bubonic plague, and hemorrhagic fever. By the end of a malaria pandemic in 1590, the pre-Hispanic population of central Mexico from Durango to Guatemala had fallen from 25-30 million to just one million. In fact, had it not been for these pandemics, history might have taken a different turn and driven the vastly outnumbered soldiers accompanying Hernán Cortes out of Mexico back to Spain. Yet, here we are.

The drawing shows Nahuas infected with smallpox disease. The illustration accompanies text written in Nahuatl, which in English translation says in part:

“. . . [The disease] brought great desolation: a great many died of it. They could no longer walk about, but lay in their dwellings and sleeping places, no longer able to move or stir. They were unable to change position, to stretch out on their sides or face down, or raise their heads. And when they made a motion, they called out loudly. The pustules that covered people caused great desolation; very many people died of them, and many just starved to death; starvation reigned, and no one took care of others any longer. On some people, the pustules appeared only far apart, and they did not suffer greatly, nor did many of them die of it. But many people’s faces were spoiled by it, their faces were made rough. Some lost an eye or were blinded.”

– Florentine Codex (1540-1585), Book XII folio 54. The Florentine Codex is a 16th-century compendium of materials and information on Aztec and Nahua history collected by Fray Bernardino de Sahagún. (Image and caption source: Wikipedia/public domain)

We first heard about COVID-19 sometime in January as news began to spread about the outbreak in Wuhan, China. It seemed a long way at the time, too far away to affect us. At the time, populist politicians in Mexico and the USA dismissed the threat as a hoax, even though the world had dodged two previous outbreaks of coronaviruses, SARS in China in 2003 (8000 cases,) and MERS in Saudi Arabia in 2012 (2500 cases.) As recently as the day before this writing at the start of May 2020, Mexican President Andrés Manuel López Obrador blamed the crisis on the failure on his political boogeyman, neoliberalism, and the US government continues to blame China for either engineering the virus or diminishing the sense of danger while hoarding protective medical equipment, even as the US revises its estimated death projection to 100,000+ and Mexico enters the peak of the pandemic, flooding hospitals across the country with the sick and dying. To say we were caught unprepared is the understatement of the century. We were not prepared at all, it turns out.

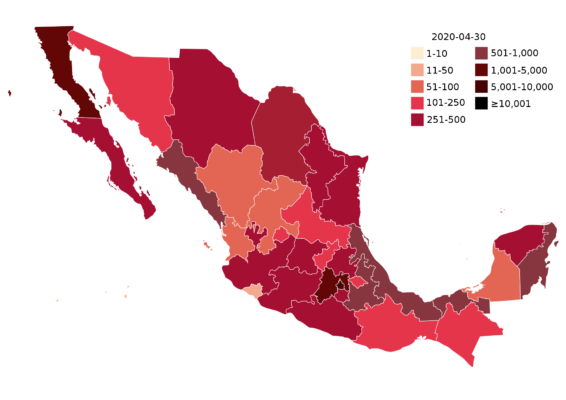

Adding insult to injury, political leaders in both countries (and many others around the world) demonstrated a lack of vision, caution and completely failed to implement preventative measures in a timely manner, choosing instead to focus on conspiracy theories and blame when the focus should have been on securing ventilators for hospitals and providing personal protective equipment to medical workers and first responders, which included retail workers of essential businesses such as grocery stores, pharmacies, banks, and food industry workers, among others. This failure of leadership, and dismissal of the seriousness of the situation by US President Donald Trump, who labeled coronavirus a political hoax after the US Senate failed to remove him from office after he was impeached in the House of Representatives, has so far resulted in 1.24 million infected in the US with 72,050 dead, and 26,025 infected in Mexico with 2,507 dead, with thousands more not counted as neither country has been able to implement widespread testing for the disease or its antibodies, which would indicate an infection from which the patient had been recovered. In truth, we’ll never know how many were infected by this virus because of the failure of political leadership in the USA, Mexico, and all around the world.

On March 23, SEP closed schools nationwide, forcing a pivot to online instruction

As the weeks passed, alarms started going off around the world as the virus first spread from China to Iran, then Italy, Spain, the United Kingdom, the United States, and finally to Mexico. By the beginning of March, people were very much aware of the impending pandemic, and a sense of panic started to emerge. We started discussing it in my English classes during listening exercises using BBC One Minute News at the school where I teach in the state of Mexico. On March 13, the Secretariat of Public Education (SEP) announced an expansion of Semana Santa, the week before Easter when much of Mexico typically goes on vacation, with schools closing on March 20 as the government started implementing social distancing measures. Out of an abundance of caution, my school, which has 11 branches in 3 states and Mexico City, decided to go ahead and close early on March 17, suspending all classes in progress as it prepared to pivot to online instruction. After a few weeks, we resumed online instruction, completing courses-in-progress as we flexed new digital skills and adapted classroom methodologies to online instruction. In the meantime, the pandemic continued to build with Mexico City and the states of Mexico, Sinaloa, and Baja California being the most impacted areas. As in other nations, the government closed down the economy on March 23 in an effort to keep workers at home, increasing social distancing, and recommended the use of masks when out in public. In my house, we started wearing masks whenever we left the house when the quarantine started. We also minimized social contact with others and reduced shopping to groceries, the pharmacy, and the bank, which we could, fortunately, do all in one stop at our nearby grocery store.

As April approached, my friends and I had reserved a penthouse in Acapulco for Semana Santa, which we were all really excited about. It would be my first visit to Acapulco, which was the premier beach destination in Mexico for many years before problems associated with narcotrafficking in the state of Guerrero landed Acapulco on the US State Department warning list of areas for American tourists to avoid. Living in Mexico for almost 2 years now, I’ve learned to take these warnings with a grain of salt and rely on the opinions of my friends here, who have a better understanding of the threats and specifically where to avoid. Their counsel has kept me safe while affording me the opportunity to venture off the beaten path to parts of Mexico I might never see otherwise. When we first heard about the pandemic and realized it might be in Mexico by the time our trip, we decided that we would make our trip, even if it meant isolating together in the penthouse, where we would still have amazing views of the beach and ocean with the comfort and convenience of a large outdoor patio and private infinity pool. Toward the end of March, after the government closed down schools, the economy, and all beaches nationwide, we decided it would be prudent to cancel our trip. We were stunned to run into problems canceling our reservation through Booking, the subject of another article, Why you should NEVER again use Booking, Priceline, or Kayak. The pandemic brought a lot of things into focus, including the fact that companies like this consider hosts their clients, not travelers, so they were belligerent and unwilling to accommodate us forcing us to negotiate a change of dates with the host, who balked when we asked to cancel our reservation without penalty due to the pandemic. We ended up being forced to process a refund through the credit card company, and will forever remember being put in such a terrible position by Booking, which along with Priceline and Kayak, we will never again use to book future trips.

As in the US, however, a lot of people in Mexico chose to ignore the warnings, either believing and acting on various conspiracy theories or demonstrating skepticism about the warnings due to mistrust of government. We watched in dismay as our neighbors continued to socialize, sitting in close proximity to strangers at our local taquerías–none wearing masks, and kids continued playing in the streets and fields as if they were merely out of school for summer. A neighbor behind us who is apparently a church minister started holding worship services at his home after the government closed churches, theaters, stadiums, and other venues where large groups gather. We watched as people sang and held hands to pray without masks, seated next to each other. We were disappointed and felt judgmental seeing all this happening around us. We couldn’t understand why people were not taking the danger seriously, failing to take reasonable measures to protect their own health as well as the health of the more vulnerable members of the community. Ultimately, we even felt uncomfortable with our own feelings of anxiety and discomfort being around people, especially if they weren’t wearing masks or intruded into the recommended 2 meters distance. This is not normal human behavior, after all, we are social creatures. It is unnatural for us to be socially distant, to mistrust each other, to feel dirty in each other’s presence, but these were the realities the situation required.

Our favorite panadería stayed open for takeout only, limiting entrance to one customer at a time.

After the pandemic reached phase 3 (widespread community contagion) on April 21, we stopped going out almost entirely, switching to home delivery for groceries and only venturing out for absolute necessity. Finally, the stores in our neighborhood started posting signs denying entrance to people not wearing government-mandated masks. Yet even then we witnessed situations of people apparently believing they were somehow special or invulnerable, and therefore exempt to public health safety measures. One night this week, I was in a panadería on my street. It’s a small business owned by an older woman who posted a giant sign, “Cubrebocas Obligatoria” (masks required), and left a giant bottle of hand sanitizer on a table outside the entrance for customers to use as they enter and leave. When I arrived, there was nobody in the store. I was wearing my mask, of course, and used the hand sanitizer as I entered. I grabbed some bolillos and brought them to the counter, then stood back 2 meters while she put them in a bag and rang up the transaction. As I was paying a woman entered. She was not wearing a mask. The owner told her she couldn’t enter without a mask. She assured the owner she just needed something quick, returning to the table to use hand sanitizer, which she had not used on her way in. I looked at the owner and said, “so many special people, aren’t there?” She responded, “¡Sí!”, glaring at the woman. As I took my purchase to leave, I turned to the woman and told her, “You know, you’re not special. You’re risking your own health as well as ours.” She seemed shocked, but I felt no regret. The truth is people like her are a risk to the health of others, however special or invulnerable they may feel, so I believe it’s appropriate in phase 3 to speak up. Hopefully, after being confronted by a stranger, the woman thought more about the safety of others in her community the next time. Hopefully.

And that brings us to the present moment. Living in Mexico during the pandemic has been an interesting experience for me. I’ve learned more about people’s relationship with the government, which has historically failed Mexico for so long that people are rightly skeptical of it. It’s also given me an interesting outsider’s view of the pandemic back in the United States. At no point have I felt like I’d be safer returning to the US. When the new US Ambassador urged American citizens to consider returning to the US, even as the situation in the US grew increasingly desperate and dire due to the failure of political leaders to respond appropriately, I literally laughed it off. For me, returning to the US would mean arriving without a job, without health care, without housing, etc. all during the middle of a pandemic. Seeing what was happening in the US, there was no way I felt safer there than in Mexico where I have a job, healthcare, a beautiful apartment, and have started building a beautiful life for myself with my partner, our two dogs, and many friends all across Mexico. From my perspective in Mexico, I feared for the safety of family and friends in the US, especially my parents, aged 72 and 80, who have conditions that increase their risk for complications if they become infected. My father had a big birthday party planned for his 80th that had to be postponed until the fall. He was really disappointed to have to cancel it, but we realized that if they went ahead with the party and all the traveling and social contact it would require, they were likely to become infected and might not make it.

By HueMan1, JTequida, and Davidmejoradas – This file was derived from: Mexico template.svg:, CC BY-SA 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=87561010

Living in a pandemic requires difficult decisions. It requires patience and perseverance. It is an opportunity for us to rise up to do our best for ourselves, our families, and communities, even though so many have failed. Protesters asserting their “rights” to carry on with their lives uninterrupted or without suffering any inconvenience to protect themselves or others seem to have missed the higher moral imperative to love their neighbor as they love themselves, even as they defiantly march off to church on Sunday without masks. As I said before, the pandemic has brought a lot of things into focus. I’m sorry to say that my faith in humanity to do the right thing in a time of crisis is completely shattered. My faith in politicians and governments to lead and inspire the people through dark times like this has evaporated. Yet, I hope that hindsight will be 20/20. I hope we learn from this experience and learn to love each other more. I hope there will be less death than I expect there to be among members of my community here in Mexico who chose to ignore the warnings. And, despite it all, I still have hope that the world that emerges from the pandemic will be a better and kinder world than it was before.